На фотографиях, опубликованных Катей Улитиной по следам ее визита в роттердамский дом Сонневельда, в компании со стальной мебелью Виллема Хендрика Гиспена в замечено кресло за авторством немецкого дизайнера Эриха Дикманна, который был незаслуженно забыт и не удостоен ни полсловом в прекрасном обзоре истории Баухауса, написанном Фрэнком Уитфордом. Хоть Дикманн, учившийся в Баухаусе в 1921-1924 гг., а после досрочно сдавший экзамены по столярному делу и преподававший эту дисциплину веймарским студентам, известен прежде всего предметами мебели из древесины, в его репертуаре было значительное количество из других материалов, в том числе стальных трубок, которые он гнул под впечатлением от работ своего коллеги Марселя Брейера, но отличным от последнего образом.

К слову, Брейер, в 1926 г. передавший Дикманну руководство факультетом деревообработки, по достоинству оценивал работу своего преемника на поприще проектирования предметов быта: «Его мебель отличается известной легкостью и ненавязчивостью, она словно начерчена в пространстве и не мешает ни движению, ни обзору»…

———

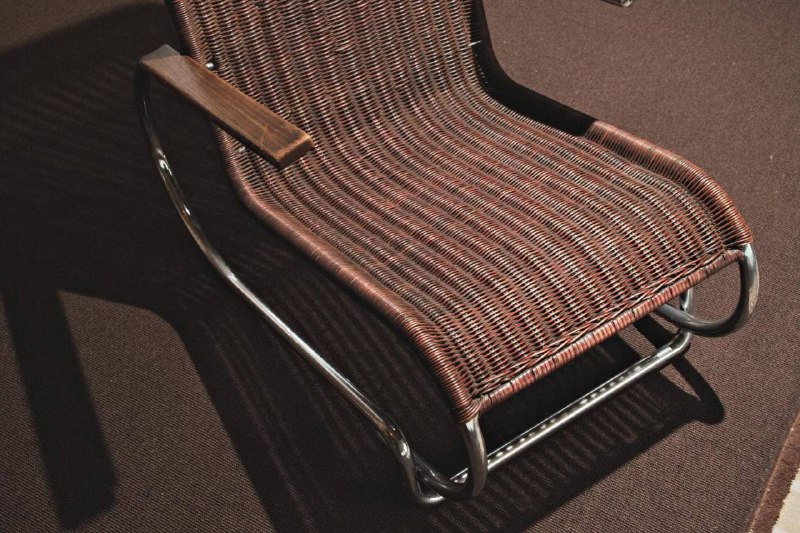

If you’ve read Katya’s account of her visit to the Sonneveld house in Rotterdam, you may have noticed a lounger amidst other tubular steel furniture designed by the Dutch Willem Gispen. This lounger is a product of an influential German designer by the name of Erich Dieckmann who was active in the 1920-1940s and has then fallen into oblivion without so much as a tiniest mention in Frank Withford’s comprehensive history of Bauhaus. A student of Bauhaus in 1921-1924, Dieckmann completed his apprenticeship as a carpenter ahead of the curriculum to begin teaching woodworking to Bauhaus students and was so fascinated by wood that it’s difficult to come to terms with his equally stunning tubular steel endeavors. His interest in bent steel furnishings was obviously inspired by one of his much better known colleagues, Marcel Breuer, but manifested itself in highly original twists and turns.

Interestingly, Breuer, whom Dieckmann replaced as head of the woodworking department at Bauhaus in 1926, paid due respects to the German designer’s vision and talent as a furniture-maker in subsequent years. Here’s what he wrote on Dieckmann’s furnishings in 1928, “They are rather light, open, as if sketched into the room; they do not hinder either movement or the view across the room."…

К слову, Брейер, в 1926 г. передавший Дикманну руководство факультетом деревообработки, по достоинству оценивал работу своего преемника на поприще проектирования предметов быта: «Его мебель отличается известной легкостью и ненавязчивостью, она словно начерчена в пространстве и не мешает ни движению, ни обзору»…

———

If you’ve read Katya’s account of her visit to the Sonneveld house in Rotterdam, you may have noticed a lounger amidst other tubular steel furniture designed by the Dutch Willem Gispen. This lounger is a product of an influential German designer by the name of Erich Dieckmann who was active in the 1920-1940s and has then fallen into oblivion without so much as a tiniest mention in Frank Withford’s comprehensive history of Bauhaus. A student of Bauhaus in 1921-1924, Dieckmann completed his apprenticeship as a carpenter ahead of the curriculum to begin teaching woodworking to Bauhaus students and was so fascinated by wood that it’s difficult to come to terms with his equally stunning tubular steel endeavors. His interest in bent steel furnishings was obviously inspired by one of his much better known colleagues, Marcel Breuer, but manifested itself in highly original twists and turns.

Interestingly, Breuer, whom Dieckmann replaced as head of the woodworking department at Bauhaus in 1926, paid due respects to the German designer’s vision and talent as a furniture-maker in subsequent years. Here’s what he wrote on Dieckmann’s furnishings in 1928, “They are rather light, open, as if sketched into the room; they do not hinder either movement or the view across the room."…

group-telegram.com/midcenturymodern/17152

Create:

Last Update:

Last Update:

На фотографиях, опубликованных Катей Улитиной по следам ее визита в роттердамский дом Сонневельда, в компании со стальной мебелью Виллема Хендрика Гиспена в замечено кресло за авторством немецкого дизайнера Эриха Дикманна, который был незаслуженно забыт и не удостоен ни полсловом в прекрасном обзоре истории Баухауса, написанном Фрэнком Уитфордом. Хоть Дикманн, учившийся в Баухаусе в 1921-1924 гг., а после досрочно сдавший экзамены по столярному делу и преподававший эту дисциплину веймарским студентам, известен прежде всего предметами мебели из древесины, в его репертуаре было значительное количество из других материалов, в том числе стальных трубок, которые он гнул под впечатлением от работ своего коллеги Марселя Брейера, но отличным от последнего образом.

К слову, Брейер, в 1926 г. передавший Дикманну руководство факультетом деревообработки, по достоинству оценивал работу своего преемника на поприще проектирования предметов быта: «Его мебель отличается известной легкостью и ненавязчивостью, она словно начерчена в пространстве и не мешает ни движению, ни обзору»…

———

If you’ve read Katya’s account of her visit to the Sonneveld house in Rotterdam, you may have noticed a lounger amidst other tubular steel furniture designed by the Dutch Willem Gispen. This lounger is a product of an influential German designer by the name of Erich Dieckmann who was active in the 1920-1940s and has then fallen into oblivion without so much as a tiniest mention in Frank Withford’s comprehensive history of Bauhaus. A student of Bauhaus in 1921-1924, Dieckmann completed his apprenticeship as a carpenter ahead of the curriculum to begin teaching woodworking to Bauhaus students and was so fascinated by wood that it’s difficult to come to terms with his equally stunning tubular steel endeavors. His interest in bent steel furnishings was obviously inspired by one of his much better known colleagues, Marcel Breuer, but manifested itself in highly original twists and turns.

Interestingly, Breuer, whom Dieckmann replaced as head of the woodworking department at Bauhaus in 1926, paid due respects to the German designer’s vision and talent as a furniture-maker in subsequent years. Here’s what he wrote on Dieckmann’s furnishings in 1928, “They are rather light, open, as if sketched into the room; they do not hinder either movement or the view across the room."…

К слову, Брейер, в 1926 г. передавший Дикманну руководство факультетом деревообработки, по достоинству оценивал работу своего преемника на поприще проектирования предметов быта: «Его мебель отличается известной легкостью и ненавязчивостью, она словно начерчена в пространстве и не мешает ни движению, ни обзору»…

———

If you’ve read Katya’s account of her visit to the Sonneveld house in Rotterdam, you may have noticed a lounger amidst other tubular steel furniture designed by the Dutch Willem Gispen. This lounger is a product of an influential German designer by the name of Erich Dieckmann who was active in the 1920-1940s and has then fallen into oblivion without so much as a tiniest mention in Frank Withford’s comprehensive history of Bauhaus. A student of Bauhaus in 1921-1924, Dieckmann completed his apprenticeship as a carpenter ahead of the curriculum to begin teaching woodworking to Bauhaus students and was so fascinated by wood that it’s difficult to come to terms with his equally stunning tubular steel endeavors. His interest in bent steel furnishings was obviously inspired by one of his much better known colleagues, Marcel Breuer, but manifested itself in highly original twists and turns.

Interestingly, Breuer, whom Dieckmann replaced as head of the woodworking department at Bauhaus in 1926, paid due respects to the German designer’s vision and talent as a furniture-maker in subsequent years. Here’s what he wrote on Dieckmann’s furnishings in 1928, “They are rather light, open, as if sketched into the room; they do not hinder either movement or the view across the room."…

BY Mid-Century, More Than

Share with your friend now:

group-telegram.com/midcenturymodern/17152