For someone considering converting to Catholicism, what questions would you put to them in order to dicern whether or not they have examined their situation sufficiently? Say, a Top 10 list.

https://www.aomin.org/aoblog/roman-catholicism/reposting-a-top-ten-list-on-roman-catholicism/

https://www.aomin.org/aoblog/roman-catholicism/reposting-a-top-ten-list-on-roman-catholicism/

Alpha and Omega Ministries

Reposting a Top Ten List on Roman Catholicism

I looked for an HOUR before I found this article, so I wanted to get it back out there where it can do some good. I wrote this in August, 2007 in response to a

Papalism

by Edward Denny

Papalism examines each of the papacy’s major claims and seeks to honestly engage with each one. Edward Denny re-establishes Christian unity by addressing major ecumenical disagreements through Scripture and church history. Papalism begins with an examination of the words, “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church,” seeking wisdom from early Church Fathers to discuss Peter’s appointment as the head of the Church. Papalism studies the testimonies of Saint Cyprian, Saint Jerome, Saint Augustine, Saint Chrysostom, and others to shed light on the claims of the papacy, and to ultimately support the stances of both the Eastern Orthodox and Anglican Churches.

https://christiantruth.com/articles/articles-roman-catholicism/papalism/

by Edward Denny

Papalism examines each of the papacy’s major claims and seeks to honestly engage with each one. Edward Denny re-establishes Christian unity by addressing major ecumenical disagreements through Scripture and church history. Papalism begins with an examination of the words, “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church,” seeking wisdom from early Church Fathers to discuss Peter’s appointment as the head of the Church. Papalism studies the testimonies of Saint Cyprian, Saint Jerome, Saint Augustine, Saint Chrysostom, and others to shed light on the claims of the papacy, and to ultimately support the stances of both the Eastern Orthodox and Anglican Churches.

https://christiantruth.com/articles/articles-roman-catholicism/papalism/

DEAD AIR experienced from Catholic apologists when asked this question about Jerome on the canon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=urMbTBeEEPw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=urMbTBeEEPw

YouTube

DEAD AIR experienced from Catholic apologists when asked this question about Jerome on the canon

During a discussion on @CapturingChristianity, Cameron Bertuzzi asked Roman Catholic apologists, Gary Michuta @ApocryphaApocalypse, @WilliamAlbrecht, & @davidszaraz4605 if there was anyone throughout church history who believed Jerome changed his mind on…

Earliest Interpretations of Revelation 12 and the Woman of Revelation 12

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2023/10/earliest-interpretations-of-revelation.html

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2023/08/correcting-sam-shamoun-and-william.html

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2023/08/autpurt-ambrose-d-784-on-ark-of.html

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2023-08-27T16:00:00-07:00&max-results=20&start=30&by-date=false

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2023-08-17T07:55:00-07:00&max-results=20&start=34&by-date=false

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2023-08-12T18:57:00-07:00&max-results=20&start=39&by-date=false

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2023/10/earliest-interpretations-of-revelation.html

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2023/08/correcting-sam-shamoun-and-william.html

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2023/08/autpurt-ambrose-d-784-on-ark-of.html

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2023-08-27T16:00:00-07:00&max-results=20&start=30&by-date=false

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2023-08-17T07:55:00-07:00&max-results=20&start=34&by-date=false

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2023-08-12T18:57:00-07:00&max-results=20&start=39&by-date=false

Blogspot

Earliest Interpretations of Revelation 12 and the Woman of Revelation 12

The four earliest (that I could find so far) interpretations of Revelation 12 either state or imply that the woman of Revelation 12 is not M...

Forgeries and the Papacy: The Historical Influence and Use of Forgeries in Promotion of the Doctrine of the Papacy

https://christiantruth.com/articles/forgeries/

https://christiantruth.com/articles/forgeries/

Josephus' Canon - A Brief Response to Gary Michuta

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2025/05/josephus-canon-brief-response-to-gary.html

http://turretinfan.blogspot.com/2025/05/josephus-canon-brief-response-to-gary.html

Blogspot

Josephus' Canon - A Brief Response to Gary Michuta

In a recent livestream (" Josephus Does Not Give a Canon "), Gary Michuta argued that a famous quotation from Against Apion , usually cited ...

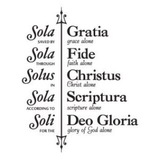

Sola Scriptura NOT Refuted w/ James R. White

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jM1G5PB4_8o&pp=ygUUUmV2ZWFsZWQgYXBvbG9nZXRpY3M%3D

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jM1G5PB4_8o&pp=ygUUUmV2ZWFsZWQgYXBvbG9nZXRpY3M%3D

YouTube

Sola Scriptura NOT Refuted w/ James R. White

In this episode, Eli is joined by Dr. James R. White to respond to 9 arguments against Sola Scriptura put out by Cameron Bertuzzi of Capturing Christianity. #solascriptura #Reformedtheology #jamesrwhite #Apologetics

➡️ Join me at Bahnsen U: https://apol…

➡️ Join me at Bahnsen U: https://apol…

Anthony Rogers Vs Seraphim Hamilton: Justification by Faith Alone

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/ln9-eWnT3Fk

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/ln9-eWnT3Fk

YouTube

Anthony Rogers Vs Seraphim Hamilton: Justification by Faith Alone #debate #bible

#Debate-------------------------------------------------------------------------------SUPPORTVenmo: https://venmo.com/TheGospel-TruthPatreon: https://www.pat...

Did Luther Want to Throw the Epistle of James in the Stove?

https://beggarsallreformation.blogspot.com/2024/12/did-luther-want-to-throw-epistle-of.html

https://beggarsallreformation.blogspot.com/2024/12/did-luther-want-to-throw-epistle-of.html

Blogspot

Did Luther Want to Throw the Epistle of James in the Stove?

Did Martin Luther want to throw the Epistle of James in the stove? Roman Catholics use this comment to demonstrate Luther's abandonment and ...

Whitewashing the History of the Church

https://www.aomin.org/aoblog/roman-catholicism/whitewashing-the-history-of-the-church/

https://www.aomin.org/aoblog/roman-catholicism/whitewashing-the-history-of-the-church/

Was Ignatius of Antioch a Protestant? | Reformed Theology in the Church Fathers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmHOOmvcm2o&list=PLN_hGgClL6DiPA5wZOYsukPu7Yt9gv-4O&index=8&pp=iAQB

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmHOOmvcm2o&list=PLN_hGgClL6DiPA5wZOYsukPu7Yt9gv-4O&index=8&pp=iAQB

YouTube

Was Ignatius of Antioch a Protestant? | Reformed Theology in the Church Fathers

Reformed theology in Clement of Rome: https://youtu.be/-zH1PLZJvns

Contrary to what some may believe, the fundamental doctrines of Protestant and Reformed theology were not inventions of the Protestant Reformers - rather, these doctrines find their origins…

Contrary to what some may believe, the fundamental doctrines of Protestant and Reformed theology were not inventions of the Protestant Reformers - rather, these doctrines find their origins…

The Protestant Canon DEFENDED (With Javier Perdomo and Cleave to Antiquity)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hwfq4r4yi6M

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hwfq4r4yi6M

YouTube

The Protestant Canon DEFENDED (With Javier Perdomo and Cleave to Antiquity)

Gavin Ortlund discusses the Protestant canon with @javierperd2604 and @CleavetoAntiquity, considering Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox objections, the testimony of church history, and more.

Javier's channel: https://www.youtube.com/@javierperd2604

Cleave…

Javier's channel: https://www.youtube.com/@javierperd2604

Cleave…

When Does Icon Veneration Become Idolatry? Protestant Answer

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/RCbD9SaIE5k

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/RCbD9SaIE5k

YouTube

When Does Icon Veneration Become Idolatry? Protestant Answer

Truth Unites (https://truthunites.org) exists to promote gospel assurance through theological depth. Gavin Ortlund (PhD, Fuller Theological Seminary) is Pres...

How Rebuttals Go Wrong: Joe Heschmeyer and the Canon Debate

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMfTqssw6k0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMfTqssw6k0

YouTube

How Rebuttals Go Wrong: Joe Heschmeyer and the Canon Debate

Gavin Ortlund responds to Joe Heschmeyer about Protestant and Roman Catholic views of the biblical canon.

Joe's video: https://youtu.be/xdaWAX8FsOs?si=RcJj3p551RCys0kr

Our original video: https://youtu.be/hwfq4r4yi6M?si=deR-g9KVFZLw-DVV

Truth Unites (h…

Joe's video: https://youtu.be/xdaWAX8FsOs?si=RcJj3p551RCys0kr

Our original video: https://youtu.be/hwfq4r4yi6M?si=deR-g9KVFZLw-DVV

Truth Unites (h…

“The Peter Syndrome.” This refers to the propensity on the part of many Roman Catholic apologists to find any statement about Peter in the writings of an early Father and apply this to the Bishop of Rome. There are many exalted statements made about Peter by men such as Cyprian or Chrysostom. However, it does not follow that these statements about Peter have anything at all to do with the bishop of Rome. The Roman apologist must demonstrate that for such statements to be meaningful that the Father under discussion believed that the bishop of Rome alone is the sole, unique successor of Peter, so that any such exalted language about Peter is to be applied in that Father’s thinking to the bishop of Rome alone. If such a basis is not provided, references to Peter are irrelevant.

One even finds the Peter Syndrome infecting the exegesis of our authors of biblical passages as well. This is easily understood: our authors belong to religious systems that demand they believe certain things about Peter and Peter’s alleged successors. These systems claim extra-scriptural authority, and hence, it is hardly surprising to find that people who hold to such systems do not practice sola scriptura, and hence do not engage in fair exegesis of the text itself. Instead, since they hold to sola ecclesia (the idea that the Church alone has supreme and final authority, which is illustrated so clearly by Rome’s claim to define the canon of Scripture as well as the interpretation thereof, and to define the extent, and meaning, of “Tradition” as well, leaving her as the sole functional authority), they will find in the text exactly what the ecclesia tells them to find.

The Peter Syndrome – Roman Catholic Writers See Papal Supremacy Behind Every Bush, or In Every Early Father”

https://www.aomin.org/aoblog/roman-catholicism/the-peter-syndrome-roman-catholic-writers-see-papal-supremacy-behind-every-bush-or-in-every-early-father/

One even finds the Peter Syndrome infecting the exegesis of our authors of biblical passages as well. This is easily understood: our authors belong to religious systems that demand they believe certain things about Peter and Peter’s alleged successors. These systems claim extra-scriptural authority, and hence, it is hardly surprising to find that people who hold to such systems do not practice sola scriptura, and hence do not engage in fair exegesis of the text itself. Instead, since they hold to sola ecclesia (the idea that the Church alone has supreme and final authority, which is illustrated so clearly by Rome’s claim to define the canon of Scripture as well as the interpretation thereof, and to define the extent, and meaning, of “Tradition” as well, leaving her as the sole functional authority), they will find in the text exactly what the ecclesia tells them to find.

The Peter Syndrome – Roman Catholic Writers See Papal Supremacy Behind Every Bush, or In Every Early Father”

https://www.aomin.org/aoblog/roman-catholicism/the-peter-syndrome-roman-catholic-writers-see-papal-supremacy-behind-every-bush-or-in-every-early-father/